Angevin England

By Rhodri ap Hywel (Rob Howell)

A contemporary chronicler tells us that William Marshal carried the royal scepter of gold in the coronation of Richard I in 1189.1

Today, we remember Richard as the King of England usually as portrayed by Sean Connery, Patrick Stewart and many others in Robin Hood film adaptations, but the truth of Richard was much different. That truth explains many of the challenges facing William and the English during the reigns of Henry II, Richard I, and John I.

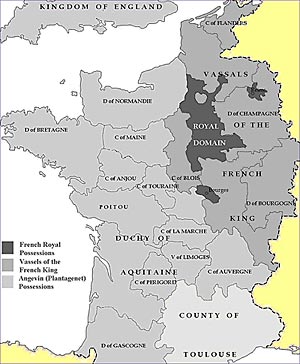

By the end of the day on 6 June 1189 Richard was not only the King of England, but was also the Duke of Normandy, the Duke of Aquitaine, the Count of Anjou, and the Count of Maine. The King of England was thus not only the largest vassal of the King of France, but as can be seen by looking at English controlled territories in France; he also controlled more land in France than did the French.

France in the 12th Century (Click map for a larger version.)

Furthermore, from Richard's point of view, in many ways England was the least of his possessions. Richard was born in Oxford, but he was essentially French. He never truly learned how to speak English and he spent only about six months of his ten year reign actually in England.

Furthermore, when he died, he specified that his body be buried in multiple places, which was not uncommon for kings at the time. Richard chose to have his brain buried in Poitou, his heart in Rouen, and the rest of his body at Fontevrault Abbey in Anjou. In other words, at the end of his life, the King of England chose to associate himself eternally with France, rather than with England. Hence, perhaps Gerard Depardieu would be a more appropriate actor to play Richard in the Robin Hood movies than Connery or Stewart.

Richard viewed England not as his home, but as a source of revenue. In the last year of his life, Henry II, Richard's father, imposed the Saladin Tithe. This called for each person to give a tenth of their wealth to support those who left on Crusade, most notably Richard himself.2 By the end of Richard's reign in 1199, such taxes such had essentially bankrupted England in order to pay for his military excursions. Ironically, one of the reasons that English sheriffs such as the Sheriff of Nottingham were so demanding of tax payments was that Richard kept demanding more and more money. The situation was exacerbated by Richard's capture and subsequent ransom on his return from the Crusades.

After Richard´s death in 1199, the throne passed to his brother John. John I was greedy, uninspiring, ineffective, and at best a mediocre King, but nevertheless, John´s reputation is further harmed by the difficult situation that he found himself in when he took the throne in 1199. He inherited a poor and overtaxed kingdom. He controlled a large portion of France, but this automatically put him into a conflict with France´s king, Philip II Augustus.

Philip was not a crusader or military figure like Richard, but Philip was one of the best kings France has ever had. Combine a mediocre English king, hamstrung by a wounded economy, in opposition to a great king and it is easy to guess what the outcome will be.

After Philip defeated John and his allies at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, the results were even worse. John was forced to strengthen his power base in England, but all he could offer his secular and ecclesiastical lords were political rights, which he did in 1215 with the Magna Carta.

![]() (Right: Phillip II known as Augustus)

(Right: Phillip II known as Augustus)

Despite the significance with which we view the Great Charter today, at the time it was not seen as revolutionary or even successful. In but a few months its failures lead to the First Baron´s War, and in 1216 John died in a failed campaign during this war. This left the nine year old Henry III on the throne.

At this time William Marshal swore oaths to protect his fourth and final king, not as a knight and earl, but as Regent and Protector of England. He is recorded to have said: “If everyone abandons the boy but me, do you know what I shall do? I will carry him on my back, and if I can hold him up, I will hop from island to island, from country to country, even if I have to beg for my bread!” 3

And, indeed, it was possible that Henry III, the rightful King of England, might be sent into exile. The rebelling barons who had opposed John had offered their support and loyalty to Louis, the son of Philip of France. The death of John had not ended the rebellion, and William the Protector had to defend England with limited resources.

In the spring of 1217, the rebels made a concerted push to finally take the royalist stronghold of Lincoln. The sources say that William scraped together 406 knights and 317 crossbowmen to lift the siege.4 With a rousing and inspiring speech, and fighting from the front far more than his advisors wished, he led these forces against the rebels and, despite numerical inferiority, led the English royalists to a major victory in the Battle of Lincoln. This battle, and the subsequent naval battle off of Sandwich, ensured that Henry III would keep his crown.

(Left: Coronation of Henry III.)

Today, we might see the English barons´ decision to support a French prince as odd. England in the early 1200s, however, was still part of the French-based Angevin Empire and was ruled by a French family who only after this point start identifying  themselves with England.

themselves with England.

The English nobility was still predominantly French in its culture and perspective. In fact, William himself was culturally French. The contemporary biography of William, the Histoire de Guillaume le Maréchal, is written in French, and he was one of Philip´s vassals as well as one of Richard´s.

So remember, when you are singing of William coming into France and winning renown with sword and lance that William was merely fighting in one of the two kingdoms – two competing kingdoms – that he called home.

![]()

1 http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/hoveden1189a.html

2 http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1188saldtith.html

3 David Crouch, William Marshal: Knighthood, War and Chivalry, 1147-1219, 2nd ed. (London: Pearson Education, Ltd., 2002), 127. This is the best of the three biographies of William. Sidney Painter´s has become severely dated, and Georges Duby´s is odd in its biases and conclusions.

4 Ibid., 129.

![]() Marshal – Flower of Chivalry • Coming to Three Rivers Memorial Day Weekend 2009

Marshal – Flower of Chivalry • Coming to Three Rivers Memorial Day Weekend 2009